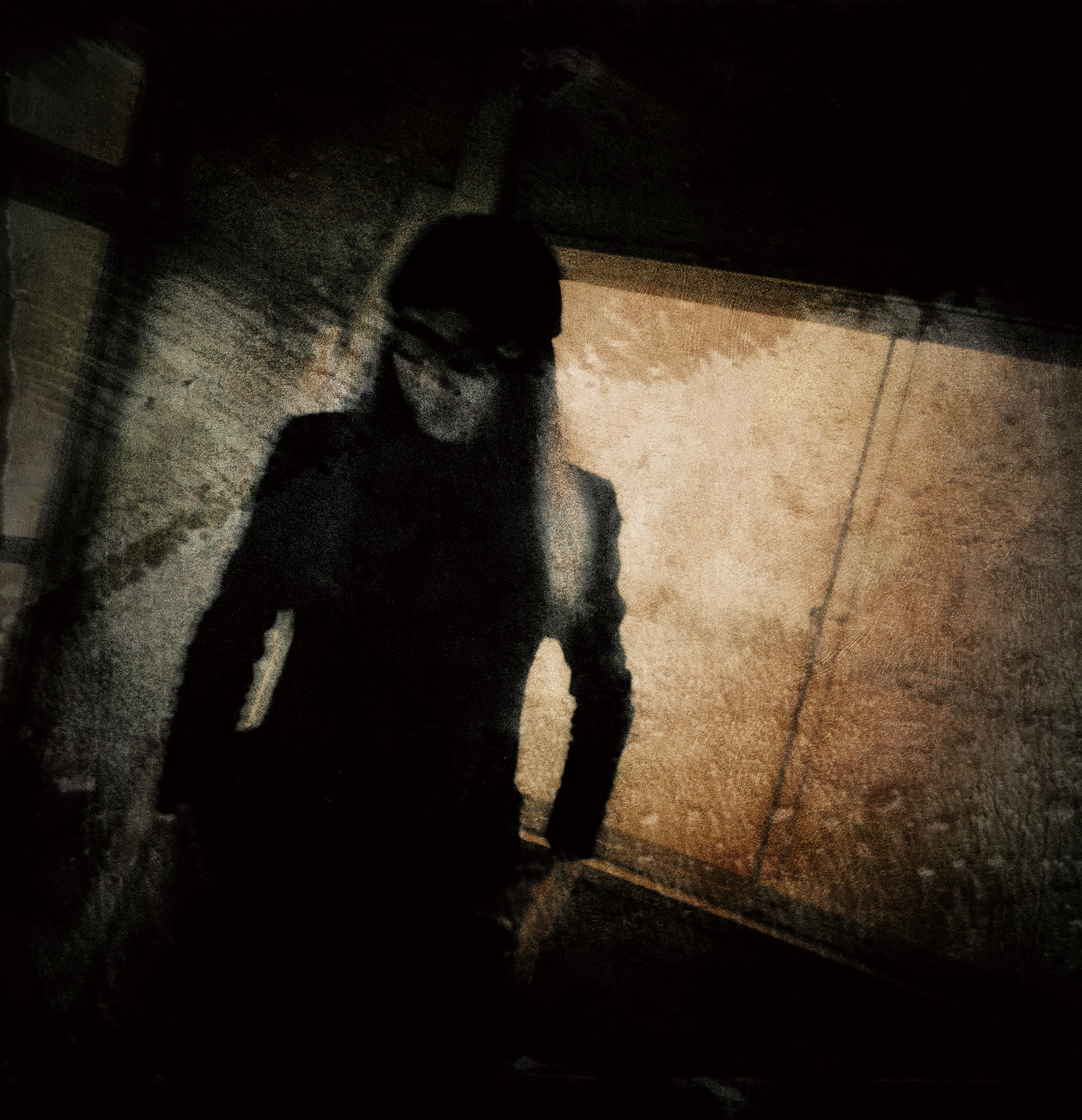

The Last One Musique

ISBN: 978-4-909856-01-2

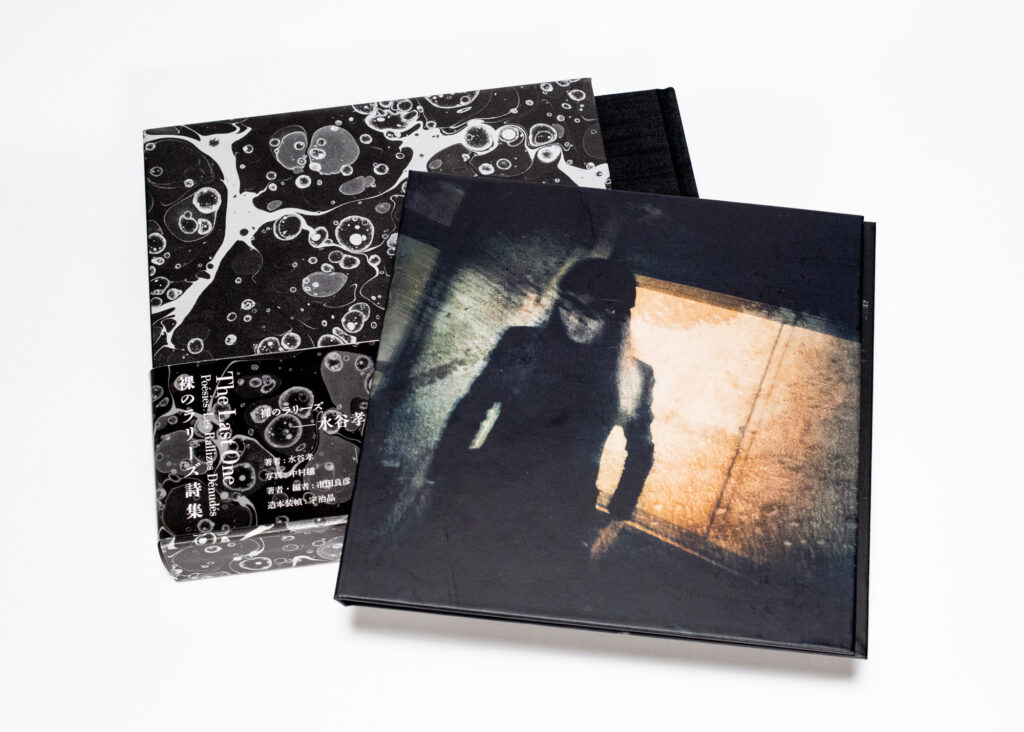

BOOK+1CD (TBVC-0006)

1. Hibiscus Flower

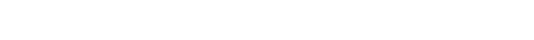

Song, lyric or poem : the world of Takashi Mizutani

Comments by Yoshihiko Ichida at The Last One Musique exhibition, December 1, 2023 (excerpts)

In 2007, I published a philosophy book in Japanese that was also a kind of music treatise. One of the chapters in the book was devoted largely to the Rallizes. In the fall of 2022, when The Last One Musique was already working on this collection and translating the poems into English, I was asked if I would help translate the poems into French. My friend Sosi Suzuki, who contributed an essay to the book, was my liaison. When I first heard about the project, my first thought was, “Can I do this?” Not only did I have doubts about whether I could do this or not, at the same time, I had doubts about whether I would be able to turn “this” into a proper French-language poem. Going through a few verses in my mind, I thought, “What does this even mean in Japanese? What kind of poetic dramaturgy is this?” My mind was full of doubts. To give one example, what is the “one” in “The Last One,” that quintessential LRD that puts the final mark on every Rallizes concert? Is it a person, is it a thing, is it a song?! Without being able to know this, or at least having some seed of the meaning interpreted correctly, from which it is possible to make some sort of decision, the poem cannot reproduce itself in a foreign language. And so I conveyed my doubts about taking on this translation.

What made me determined, even with such doubts, to take on and fulfill this job was the conviction that Mizutani’s world of words had been crudely handled, carelessly translated into haphazard English, and disseminated just like that, without care, around the world. The official recordings released by Mizutani did not include any lyric sheets. This was surely because of Mizutani’s belief that his words become “works” only once they are put to sound. Now, however, that Les Rallizes Dénudés has become world famous, I wonder, conversely, if Mizutani’s words, indivisible as they were from the music, have not been left behind. I have seen some rather appalling English translations of his words.

The biggest source of my apprehension, however, was that I was not even sure how to ascertain the original Japanese lyrics. Even what we assume to be the same song, Mizutani sang in different ways at different times. We held many discussion sessions, bouncing back and forth repeatedly between the Japanese, English, and French, finalizing the text in all three languages at the same time.

The most crucial thing was to listen to the three officially released works over and over again. The way the songs were sung was one reference for determining the text. However, as you can imagine, it is not a simple thing to determine how to link the lines of a stanza, when translating a poem, or what to do with differing Japanese kana (phonetic) or kanji character notation — if you interpret the phonetic pronunciation into the wrong kanji character, it becomes a completely different word, and so on. To start, there were many parts in which the original words could not be easily distinguished. We referred back to Mizutani’s creative notebooks as well as searched out the testimonies of people involved with the band, to find out what he told the people around him. So, in any case, even the original Japanese lyrics had to be reconsidered from zero. For example, there is a song called Zouka No Genya (“Wilderness of False Flowers”). Is it zouka meaning artificial flowers, or zouka using a different character, meaning creation, nature? By digging back to Mizutani’s notes, it could be determined as the first zouka, using the character of flower.

What I found extremely interesting was that that there were so many linked details that could only be discerned with the translation of the Japanese into French. As the translation process evolved, I found myself thinking, “Hey, doesn’t this word have a specific source in French poetry?” more and more often. Of course, Mizutani almost never used his favorite poets’ words verbatim. Still, if you take, for example, the words “the drop of nothingness” in “The Night, Assassin’s Night” and translate them into French as “la goutte de néant,” you can’t help but imagine that it comes from Symbolist poet Mallarmé’s Igitur. Despite my not being deeply familiar with literature, it is well-known enough that the connection stood out to me. No matter which way I read Mizutani’s poem, from the French perspective it couldn’t help evoking Mallarmé. I started to trace this chain of evocations back through the literature, digging deep into Mizutani’s notebooks and library to find out what he knew, and to let the French translation come to light in this way. In the course of my own research, I learned that Mizutani had been a member of the “Poetry Study Group” of Doshisha University before starting his band. He was a poet, who started out in poetry and went on to pursue a career in music, a poet in his own right. My work was therefore a retracement of his steps. To be honest, I had never thought that at my age I would be rereading Baudelaire and Lautreamont in great detail, in both Japanese and French.

Anyway, for my part, I would like to say this. The book contains “poésie,” poems designed to form a linguistic universe, not “lyrics” meant to be an accessory to music. At a certain point, the poems become more and more interconnected, and can be read as a series of poems as a whole. I am personally quite interested in how this book will be received by French literature lovers. But I am also confident that Japanese readers will also appreciate this “poésie.” I wonder if such a poem has ever been made into a rock song, or sung as a rock song. This said, we live in an age when Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Why should we not take Takashi Mizutani’s words, when combined with sound, as forming a work of “literature” of a kind that has never been read or heard before? As I neared the end of my year-long work, I became more and more convinced of this. I have no doubt that you will share these thoughts as you read the poems and listen to and re-listen to the many sources.

I will leave the poetry to you to read, but today I would like to introduce a few points in the book that will give you a sense of how Mizutani poured his heart and soul into his poetry and how he sharpened his nerves to the words themselves.

First, at almost the very beginning of Mizutani’s only video work, a part of Lautreamont’s The Songs of Maldoror is quoted in French. It is a strange excerpt, to say the least, to use as a quotation. Even reading to the end, it still isn’t clear what the “this” in “Il faut que tu me le dises” (You must tell me this) actually means. But if you unravel Lautreamont’s original text, the answer is easily found in the uncited lines. I won’t go into it here, but under Mizutani’s directing, it is as if the “this” is also an answer to what are Les Rallizes Dénudés. It is a kind of silent discourse (giving meaning to silence), the quotations a brilliant way of linking the unseen text with the sounds and images that are about to follow. When I realize the cleverness of this technique, I was amazed. How intricate! This was the moment when I realized that such tricks must be everywhere in Mizutani’s poems.

In the postface, I proposed the hypothesis that the entire album ’77 Live could be “read” as Mizutani’s reply to Mallarmé’s unfinished magnum opus, Hérodiade. As you may be aware, the Igitur mentioned earlier is a study for Hérodiade. Of course, references to the Spanish poet Lorca and echoes of Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil can also be heard in the album, but in any case, I read ’77 Live as a whole as echoing Mallarmé more than anyone else, creating its own poetic universe. Perhaps even before Mizutani himself was clearly aware of it. My impression may be a product of my own delusion, or a delusion caused by over-immersion in the French language, but I have written the postface in a bibliographic manner to the best of my ability. I am a scholar, after all. There was no intention to fill in the parts I did not understand with my imagination. I would like to ask readers not only of Japanese but also of English and French to verify themselves whether this is really the case. However, if you go back and forth reading the poems and the postface in tandem, I believe that the book will be a guidebook to the labyrinth that is “Les Rallizes Dénudés,” that Mizutani himself constructed. At the very least, you will be able to retrace my wanderings once stepped into the labyrinth. What is or is not at the back or center of the labyrinth does not seem to be something for me to say. As the editor, my only wish is that the reader will read this book and appreciate the live performance of Les Rallizes Dénudés on a deeper level. But I must go a bit further to add, Takashi Mizutani was undeniably an “artist” who was able to open the center of this labyrinth, in which another mysterious box with unknown contents is placed, as his “work of art.” Be that “work” music or poetry.

The photo of Mizutani’s creative notebook taken by Nakamura is also included in the poetry book. In my opinion, what is noteworthy is that this page of the notebook seems to be one piece of evidence. Evidence of what? It is evidence that Mizutani did not write each song separately. None of the songs are independent pieces. He was literally generating the words he sang at each live performance from a group of such verses. This is why the distinction between songs is so indistinct. The same verses can be placed on different chord progressions and melodies. When the verses are differentiated as separate songs, it gives the impression of a series of rooms in a labyrinth. And from the note on the left side of the photo, we can also see that there was a visual image behind the song. Memento mori, “Remember you must die,” is one of the motifs of Mizutani’s poems. There was no so-called “setlist” for the Rallizes’s live performances. From the loosely defined groups of verses and of sounds, Mizutani would choose, each time, on the spot, the combination of verses and sounds that suited his mood. He was like a medieval minstrel. Or like Homer or Hesiod, who appeared at every street corner to tell “stories” (songs) of the gods and people in the days when Greece did not yet have a writing system that could be used outside the court. So in any case, I was a bit moved when I saw this note on the photo. Again, Les Rallizes Dénudés are a rock band — of the 20th century. It is an extreme cohabitation of zeitgeist and antiquity, of unwavering word-for-word precision and unrestrained improvisation. It is a situation that seems to contradict our common modernist attempt to compile a collection of poems as a definitive text, but I believe that there is also a lack of boundary between the songs that can only be seen when the songs are made into written text (écriture). Of course, it is therefore also possible to interpret the poems differently than how I present them in the postface. I believe that there are still many buried chains of poetic images and relationships of influence. As the editor, I cannot help but hope that this collection of poems will be a starting point for active discussion of these points.

Finally, I would like to make a brief mention of the accompanying CD, of the song titled “Hibiscus Flower.” It is, of course, (in Japanese), pronounced “HI-biscus.” However, Mizutani sung it as “I-buscus” (French pronunciation). Mizutani deliberately pronounced it in the French style. Why is that? Perhaps it is a tribute to the film of Cocteau, whom he loved. The film is Testament of Orpheus. In this film, the “ibuscus” is the symbol of the poet’s soul. It is plucked from the bottom of the sea by the poet’s lover Séjest and handed to the poet. On the pamphlet for the April 26, 1969 performance at the Sagittarius Theater in Kyoto, the performance associated by Mizutani with this song, he wrote the following passage from François Villon’s The Testament (see liner notes for details): “Whether Paris’ or Helen’s death, Whoever dies, he feels such pain,That he lies gasping for each breath, His gall bursts forth under the strain.”

“We” — I presume to say in the plural — would like to present this book to you as the testament of the poet Takashi Mizutani.